Your spine is made of 24 moveable bones called vertebrae. The lumbar (lower back) section of the spine bears most of the weight of the body. There are 5 lumbar vertebrae numbered L1 to L5. The vertebrae are separated by cushioning discs, which act as shock absorbers preventing the vertebrae from rubbing together.

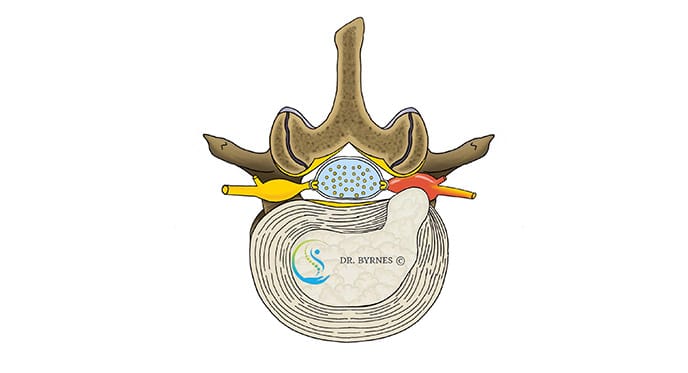

As we have described above the intervertebral discs are comprised of a leathery outer layer termed the annulus fibrosus and a softer jelly-like central component termed the nucleus pulposus. The slowly progressive degenerative process results in the gradual mechanical deterioration of both. The central nucleus polposus slowly loses it's ability to hold onto water and becomes increasingly dehydrated and reduces in volume and height. Fissures can appear within it's substance.

The outer annulus, which is made up of sheets of fibers in varying orientations is, in health, extremely strong and able to contain the nucleus even when place under significant pressure. With time however the fibers of the annulus deteriorate and can become incompetent. Stretching or tearing of these fibers can allow the central nuclear material to herniate out of position.

At each disc level, a pair of spinal nerves exit the spine primarily subserving sensations in your lower limbs and pelvis. Irritation of these nerves generally results in symptoms perceived in the distribution of the nerves rather than solely at the site of the nerve compression in the back. Lumbar Disc herniation can press on these lumbar nerve roots resulting in symptoms of pain, weakness and sensory disturbance in the lower back, buttocks, groin, thigh, lower leg, calf and foot. In fact a few patients will describe severe leg pain and numbness with little or no pain in the back. Lumbar disc herniation is one of the most common causes of lower back pain when associated with leg pain.

A large herniated disc may compress the critically important central nerves, called the cauda equina (the horse’s tail of nerves). These are the nerves that control the function of the bladder and bowel and are especially vulnerable to damage. Symptoms include: A change in your ability to control the bladder / bowel or passage of urine. Numbness around or under your genitals, or around your anus or buttocks. Sciatica, often on both sides. Weakness or numbness in the legs that is often severe or getting worse. Any of these symptoms should be treated as an emergency.

Different words may be used to describe a herniated disc. A bulging disc occurs when a broad region of disc pushes outwards. Disc protrusion or extrusions describe more localised disc herniations which can often result in more severe nerve compression and pain. A herniated disc can be described as contained or ruptured when the disc annulus tears or ruptures, allowing the gel-filled centre to squeeze out. Sometimes a ruptured disc herniation is so severe that a free fragment occurs, meaning a piece has broken completely free from the disc and is lodged in the spinal canal. This process is called sequestration.

In addition to pain, you may have leg muscle weakness, or knee or ankle reflex loss. In severe cases, you may experience foot drop (your foot flops when you walk) or loss of bowel or bladder control. If you experience significant leg weakness or difficulty controlling bladder or bowel function, you should seek medical help immediately.

Disc Prolapse is most common in people in their 30s and 40s, however it can occur at almost any age. Adults appear to be at slightly greater risk if they're involved in strenuous physical activity. Discs can bulge or herniate because of injury, heavy lifting or simple strain. Even coughing or sneezing can result in disc prolapse. Aging and it’s degenerative effects play an important role (see above). Underlying spinal mechanics, some occupational and recreational activities and potentially genetic factors may lead to early or accelerated disc degeneration.

As with all complaints, a detailed medical history and description your symptoms, any prior injuries or conditions, followed by a physical examination will help determine the cause of the symptoms.

Thereafter one or more tests or imaging studies maybe requested: X-ray, MRI scan, CT scan, and/or EMG. If there are no worrisome symptoms or neurological abnormalities advice and treatment may proceed without need for any tests or scans.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan is very safe test that uses a strong magnetic field and radio waves to give a detailed view of the soft tissues of your spine. The nerves and discs are clearly visible. It may or may not be performed with injection of a dye (contrast agent). An MRI can detect which disc is damaged and if there is any nerve compression. It can also assist in the detection of bony spurs and provides a truly detailed description of the current anatomy.

Computed Tomography (CT) scanning acquires X-rays in multiple directions to make 3-dimensional images of your spine. This test is especially useful for detailing the anatomy and underlying bony degenerative processes.

Electromyography (EMG) & Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS). EMG tests measure the electrical activity of the nerves and muscles. Small needles are placed in your muscles, and connected to a computer. Severe nerve root compression may be identified with EMG. NCS measures how well electrical signals pass along the nerve. These tests can detect nerve dysfunction or damage. Results are often normal until nerve damage is somewhat advanced.

Conventional X-rays will show the bones of the spine, the heights of disc spaces (loss of height is suggestive of disc degeneration) or whether you have arthritic changes, bone spurs, or fractures. It's not possible to diagnose a herniated disc with this test alone. Xrays taken with the patient bending forwards and backwards are particularly useful to identify spinal instability.